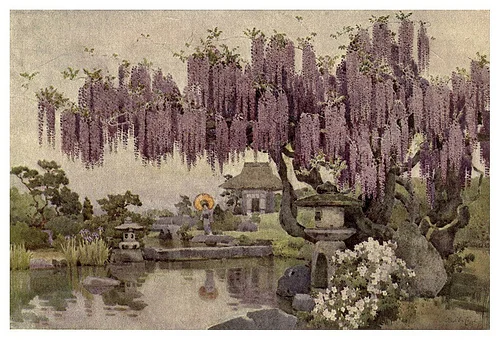

Wisteria is a fantastic flowering vine with a long history in Asian, English, and American gardens. There are many different cultivars available and most are bred from either Asiatic or American species:

Wisteria sinensis – Chinese Wisteria

Wisteria floribunda – Japanese Wisteria

Wisteria frutescens – American Wisteria (East Coast native)

Wisteria macrostachya – Kentucky Wisteria (Southeast native)

Wisteria is also wonderfully versatile. While the plant can get to storied proportions (the largest reported wisteria dates from around 1870 and covered roughly half an acre as of 2008!), it can be easily contained, and is immensely trainable as a shrub, a standard or tree form, a bonsai, or a vine. Wisterias are also fantastically cold-hardy; some species can be grown in Zone 4, with cultivars like 'Blue Moon' hardy down to -40 F!

When planted, careful consideration should be taken to ensure an adequate structure is being used, such as a sturdy arbor, pergola or fence, as wisteria can become quite heavy and requires sturdy supports.

Wisteria will also need some guidance in the form of winding or tying the young vine to the vertical structure. This can be accomplished by gently winding the young shoot around the wooden post of an arbor, pergola, or fence. You will not want this to be very tight against the wood because this trunk will swell over time. Alternatively, you can run a string from the base of the plant up to the top of your structure to train the branches to grow vertically. You can remove it once the vine has settled in on the top portion of your structure; wisteria is happy to scramble across a horizontal surface.

In much of garden literature, you will find claims that the American hybrids are less tenacious or less inclined to bloom repeatedly. However, 'less tenacious' is a very relative term. After all, we're still dealing with wisteria; healthy specimens can grow five to ten feet in a single season. As for flowering, under ideal growing conditions, and with the correct species for your climate, you will typically get a large flush of spring flowers and often another flush later in summer (usually at about thirty percent of the volume of the spring bloom).

A well-established wisteria should be in its bloom cycle in April/May here in the Northwest, with Chinese varieties blooming prior to leaf-out and American and Japanese varieties blooming after leaf-out and slightly after Chinese cultivars. Very well-tended wisterias will sometimes bloom at other times during the growing seasons, but never to the magnitude seen in spring.

Some of you may be shaking your heads thinking: mine has never even bloomed once! This is certainly possible and may be related to one of the following issues:

High-nitrogen fertilizers: If your plant is near a fertilized lawn or if you use a very high-nitrogen fertilizer (strength of nitrogen, phosphorous and potassium (N-P-K) is listed numerically on packages, with nitrogen being the first number), you will be pushing a high degree of vegetative growth at the sacrifice of flowering. Wisteria is a member of the legume/pea family and as such may have some nitrogen-fixing properties, further compounding the fertilizer factor.

Light: While wisteria can be grown in part-shade environments, flowering requires at least six hours of sunlight.

Frost: As with many spring-flowering plants, a cold snap or frost can damage and kill flowers or their buds.

Pests and Disease: This is very unusual. The biggest pest is wisteria scale, which is not a very big problem here in the Pacific Northwest. I've seen only one case of wisteria scale brought into Swansons. Treatment is best done through systemic insecticides because, given the size of wisteria plants and the density of the foliage, foliar applications are often inadequate. Sometimes root rot or graft failure can occur if wisteria is planted very poorly or grown in excessively wet locations with poor drainage.

Water: Wisteria prefer moist, fertile, well-drained soils. Thus, given our drier Mediterranean summers, some degree of irrigation can help, especially if the plant is in a particularly dry area.

Pruning: While wisterias are famous for tolerating all sorts of aggressive pruning, poorly timed or poorly done pruning can greatly mitigate flowering.

Maturation: Plants are usually said be “adults” once they've reached the capacity for flowering. For some plants this can be in a single season, or it can take decades. Wisteria grown from seed can take 20 years to bloom. Fortunately, this is very uncommon in the nursery trade. The plants we see, particularly hybrids and cultivars, are grafted or grown from rooted cuttings and will bloom quite young, at around 7 years old.

If you planted wisteria this year (or even a few years ago) and it didn’t bloom, don't worry too much. Wisteria can take time to become established and consistently put out its spectacular flower show. Very young plants may need up to 7 years before they flower freely. I have, however, come across accounts of plants flowering the first year of planting. Fortunately, growers typically make the plants available to us when they are 4-8 years old so you won’t have to wait long for blooms once properly planted.

However, if you've got an older plant that refuses to flower, or flowers only sporadically (i.e. once every few years), there are several things you can do to provoke flowering the next year.

I'll start with the basics: fertilizers and root pruning. In the second part of this series, I'll go into pruning, which is far and above the best method to promote re-blooming.

Fertilizing

The N-P-K reading on fertilizers indicates the levels of nitrogen, phosphorous and potassium they contain. Nitrogen is used primarily for the production of vegetative growth. Phosphorous and potassium are used for a wealth of plant functions, but are often understood to be tied to flower development.

Note: it is misleading to say, “Phosphorous makes flowers.” It alone does not; instead bloom formulas or superphosphate fertilizers essentially deny a plant a dose of nitrogen and shift growth from vegetative to flowering.

Give wisteria too high a dose of nitrogen – say if it’s catching fertilizer you broadcast onto your lawn (lawn fertilizers are typically quite high in nitrogen) – and flower production will suffer, but vegetative growth will be prolific.

Sometimes giving wisteria a bloom fertilizer – a generic term for any fertilizer high in P-K but low in N - can help provoke bloom, or create a fuller bloom. This should be done in early spring.

Repeatedly feeding an established wisteria is not recommended. Oftentimes, for established plants or reluctant bloomers, a healthy dose of stress helps to induce flowering.

Root Pruning

Sometimes flowering plants and trees simply languish and the reasons are mysterious or unclear. If you are having trouble deducing a cause, root pruning may sufficiently shock a wisteria into bloom.

Fear not! This does not involve digging up your plant, which is a great thing because wisteria does not transplant well, particularly later in its life.

Root pruning is best done in late fall or early spring. This technique puts the plant through a mild degree of shock, ideally provoking enhanced performance.

The best place to start root pruning is anywhere two feet away from the trunk. Drive a spade or shovel straight into the soil; you'll want to penetrate at least one foot deep. Cleanly remove the blade, move the spade roughly 14 - 18 inches to the left or right and push it in again, making sure to maintain a distance of two feet from the trunk. With your first circle made, move out another 18 inches and start in a space where you didn't go into the ground the first time – continue this staggering method to create roughly five concentric circles around the base, assuming you have a well-established wisteria.

While not an ideal approach, this method can certainly be employed on troublesome plants. Don't worry about harming the wisteria. Provided it is in good health, its highly vigorous nature will certainly help it continue to thrive even if you resort to this option.

Stay tuned for part 2 of our wisteria tutorial: Promoting Wisteria Bloom, Part 2: A 3-Year Pruning Plan.